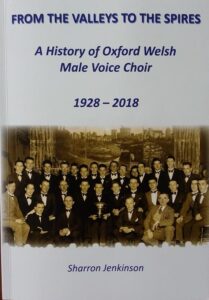

HISTORY

Richard Bedwin passed away in March 2001. He was President of our choir for the last 7 years and was Musical Director for a number of years in the 1950’s. Richard published the following as a pamphlet in 1978 as a celebration of the Choirs 50th Anniversary.

FIFTY YEARS OF SONG

A Brief History of the

OXFORD WELSH

GLEE SINGERS

1928 —1978

by

RICHARD E. BEDWIN

Dedicated to the memory of Morgan Williams, founder member and father of The Party, who passed away as this book was being prepared for publication.

CONTENTS

|

CHAPTER 1 |

SOUTH WALES 1928 |

|

CHAPTER 2 |

OXFORD 1928 |

|

CHAPTER 3 |

THE PARTY |

|

CHAPTER 4 |

PRE-WAR |

|

CHAPTER 5 |

WAR |

|

CHAPTER 6 |

POST-WAR |

|

CHAPTER 7 |

PROPOSED AND SECONDED |

|

CHAPTER 8 |

JUBILEE |

Introduction

The story of the Oxford Welsh Glee Singers is a link in the chain of Oxford’s history for half a century. Connecting links are the rise of the motor industry, in which many of the singers have spent their working lives, and the growth of trade union power and influence in the Cowley car factories. Others will tell the stories of Morris Motors, Pressed Steel and British Leyland, and of the big unions at Cowley; their dramatic tales will be studded with stars from the world of politics, big business and the T.U.C. The story of the Oxford Welsh Glee Singers is not studded with big names, nevertheless the survival of a cultural tradition in an alien society for so long suggests a story worth telling

This is the story of the car makers and trade unionists whose off-duty pleasure is found in singing. Putting together a car is a collective enterprise; putting on a choral concert is a collective enterprise, implicit in the singers’ self-styled title The Party. It is a title without political connotations, but it symbolises the team spirit which pervades their music-making. Membership of The Party bestows a very special kind of fellowship which has stood the test of time. This is the story of The Party.

R.E.B. Witney 1.4.78

South Wales 1928

The brief economic boom immediately after the 1914-1918 war was followed by the worst depression in British history since the Industrial Revolution. The “land fit for heroes” boasted one and a half million heroes on the dole, and nowhere was the anguish and despair more keenly felt than in the mining valleys of South Wales. The economy of the valleys was based upon the “black gold” hewn from the bowels of the earth, and exported all over the world. By the early nineteen-twenties the loss of export markets and the increasing use of oil fuel by the merchant navies of the world had rendered coal mining uneconomic. The industry was badly in need of mechanisation and rationalisation, but Government and mine owners were at odds over the future of the industry, and many collieries were closed. Proposals to nationalise royalties and pay a subsidy to the owners were considered and rejected. The growth of electric power removed the necessity for industries to be sited adjacent to coal mines, so that many post-war new factories were built near London and in South-east England. The transition from dangerous mine to demoralising dole queue was an experience shared by families and friends in every smoking Welsh valley. Small wonder that the emancipation of the manual worker continued to be led by the miners. The General Strike of 1926 lasted nine days; the miners’ strike of the same year lasted nine agonising months.

The social implications of this economic disaster are vividly portrayed in Richard Llewellyn’s “How Green was my Valley” – unemployment, squalor, starvation, strikes and lockouts, violence and brutality, bitterness and despair, the disruption of family life, the unacceptable face of capitalism, and the survival of body and spirit against impossible odds. The failure of Government to face the realities of the situation was enshrined in the infant National Insurance Scheme, totally inadequate to provide for the basic needs of the unemployed, placing an intolerable burden on local authorities with high levels of unemployment, and therefore least able to provide. Baldwin’s Government was aware of the problem, but unemployment was just one symptom of the terrible malaise which gripped society in the twenties. The proposed solution to the plight of the mining industry was to invite the miners to accept a reduction in wages, and work an extra hour a day. One wonders how the miners of 1978 would greet such a proposition. South Wales could be forgiven for thinking that it was forgotten by Westminster and Whitehall, despite the presence there of its most famous son, Lloyd George.

The history of South Wales between 1914 and 1945 has been described by Gwynfor Evans, President of Plaid Cymru, as “a catalogue of war and depression”. Nye Bevan, the volatile member of Parliament for Ebbw Vale, 1929-1960, described how he returned to Tredegar in 1921 after a period at the Labour College in London, and spent the next three years on the dole. By 1930 unemployment in South Wales reached a staggering 33%, despite the steady drift of young men away from the Principality. These young men, growing up in an environment of despondency and despair really had two choices – to join the dole queue, or leave home and look for work and

self-respect elsewhere. Some scraped together sufficient to buy tickets to various parts of the British Empire or the Americas. Others sought work nearer at hand, in the larger English cities where new industries were beginning to flourish. Some travelled by train, others cycled or walked, sleeping rough or in work houses and doss houses en-route. They left home with an understandable bitterness in their hearts, a bitterness in which was sown the seed of industrial strife for fifty years to come.

Bitterness often breeds violence unless there is some safety valve. A job, a girl friend, marriage, family life, putting down roots in a new society, these are recognisable safety valves; but to the young men on the move from the valleys in the nineteen-twenties they were beyond reach. Yet many of these Welsh men enjoyed a priceless safety valve, developed in home and chapel, in eisteddfod and Gymanfa Ganu: the gift of song is a tranquilliser beyond price. Welshmen forget their bitterness and despair when they unite in song, whether on the terraces at Cardiff Arms Park or in the chapel choir. Some of these singing Welshmen arrived in Oxford, searching for work, in 1928, and have been there ever since.

Oxford 1928

Oxford, the ancient University city, insulated for centuries from the harsh realities of commercial and industrial life, its economy based on the needs of the colleges and the endless stream of tourists, was stirring uneasily as the monster on its eastern outskirts grew lustily under the leadership of W.R.Morris, later Lord Nuffield. The year began with the Great Snowfall, the worst in living memory; mountains of frozen snow were removed from city streets to Port Meadow and Headington Hill Park. The thaw which followed caused widespread flooding in the lower parts of the city. In the first three months the city paid its tribute to the passing of three prominent figures – Earl Haig, Lord Oxford and Asquith, and the Earl of Abingdon. Oxford University lost the boat race by ten lengths, and the publication of the Oxford English Dictionary, begun in 1884, was completed with the issue of the final volume, Wise-Wyzen. Lord Gray of Falloden was elected Chancellor of the University, and the late Jimmy Dingle patrolled the streets of the city, advertising Grimbly Hughes’ 1921 vintage Burgundy at 60/- per doz. bottles. On the 26 November property all over the city was damaged by the worst gale since 1881. The Oxford Journal carried a brief report of an event which was to have consequences as far-reaching as the invention of the internal combustion engine; the first television transmission, between London and Harrow, was successfully completed. The Electra Cinema reopened its doors after a refit, films featuring Harold Lloyd, Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton drew the crowds. The Oxford Playhouse in the Woodstock Road attracted good houses. The repertoire included Shaw’s “Arms and the Man”, Wilde’s “The Importance of Being Earnest”, and Goldsmith’s “She Stoops to Conquer”. Among the young actors making their early reputations at the Playhouse were Richard Goolden and Robert Morley. On the 10th March the Oxford Orchestral Society celebrated its 25th Jubilee, the celebratory concert under Sir Hugh Allen included a performance of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, in which the soloist was Marie Wilson. In May the young Segovia came to Oxford for the first time and gave a guitar recital at the Town Hall. Music lovers welcomed the French composer Ravel who was awarded a doctorate of music by the University, and just before Christmas an audience in the Town Hall was entertained by one of the most distinguished instrumental trios ever assembled — Cortot, Thibaud and Casals.

W.R.Morris was by this time a generous benefactor to the city. As President of the Radcliffe Infirmary he chaired the appeal for £120,000 to build an extension, pledging £40,000 himself, if the community raised the rest. In 1929 his master company, Morris Motors (1926) Ltd. declared profits of £1,335,0O0 on a capital of £5 million. W.R. Morris personally owned the equity capital of £2 million, but paid himself no dividend. After paying the dividend on the £3 million preference capital, £950,000 was ploughed back into the business. Clearly the company had no cash flow problem fifty years ago. Oxford was struggling even then to come to terms with the motor car; every week people from all walks of life were summoned in the Magistrates Court for a variety of motoring offences – obstruction, dangerous driving, no lights, no licence, exceeding the 20 m.p.h. speed limit. The Oxford Illustrated Journal carried a regular weekly column headed “Accidents on the Roads” and the casualty department at the Radcliffe Infirmary was kept busy dealing with victims of the motor menace. It is doubtful if the implications of this rapidly growing industry for the economy of the city, the county, and indeed the country, were properly comprehended in 1928. Industrial relations in the industry were rudimentary and remained so until the arrival from Swansea of Jack Thomas, who was appointed the first secretary of the Oxford Branch of the Transport & General Workers Union in 1936.

Although Cowley has now been swallowed up in the greater Oxford conurbation, it has an ancient history as a separate community. The Romans operated a pottery there from the 1st to the 3rd century A.D. Cowley derives its name from the Anglo-Saxon Cufa’s wood or clearing, The boundaries of the parish changed from time to time, at different stages in its history it included the manors of Temple Cowley, Church Cowley, and Middle Cowley, the last centred around the present Hockmore Street. St Bartholomew’s Hospital was founded in the reign of Henry I to care for lepers; the chapel, much altered. externally, still stands. In the 12th century the trades of skinner, tanner and weaver were carried on in the parish. There is evidence to show that stone was quarried there in the 14th century. At the beginning of the 17th century Oxford and Cowley were still separated by treacherous marshes; Cowley Road, then called Berrye Lane, crossed the marsh on a causeway. In 1644 King Charles I was in occupation of the city, Cromwell was harrying Royalist troops at Islip and Bletchingdon, and on the 21 May the university and town regiments were mustered on Bullingdon Green on the northern outskirts of the parish. In the early 18th century supplies of wood fuel were augmented by peat, cut from Cowley Marsh in the spring of each year and dried for use the following winter. In the 19th century the staple industry in the parish was farming, but the village was being drawn into the Industrial Revolution. In 1864 the Wycombe Railway Co. opened its Oxford – Cowley – Thame line which was taken over by the Great Western Railway six years later. In 1868 John Allen & Co., makers of steam ploughs and traction engines opened its workshops. Cowley Barracks was built in 1877. So into the 20th century, when industry moved into the parish on a major scale, led by W.R.Morris who took over the old military academy for the assembly of cars in 1912. The First World War accelerated the development of the motor car, the Morris factories expanded and were joined in 1926 by the Pressed Steel Co Ltd., makers of car bodies. In 1928 The M.G. Car Co., under its general manager Cecil Kimber opened another factory in Cowley, where the M.G. cars were first assembled; the Morris Motors engine was specially tuned to give the extra power for which the M.G. marque is famed. Cowley was still a village, separated from Oxford by green fields arid swamps. Oxford stopped at Magdalen Road, Cowley Marsh was still undrained and flooded every winter. The vast acres of the Florence Park housing estates were still green meadows. In that year began the long negotiations in local government and Westminster which led to the extension of Oxford boundaries to include, among others, the parish of Cowley. One of its great characters, the Reverend George Moore, described as Cowley’s farmer vicar, represented the parish in these negotiations; regrettably he died and was buried in May 1928, a year before the boundary extensions were ratified by Parliament.

The plight of the South Wales mining communities was being brought to the notice of Oxford’s citizens in a number of ways. In August 1928 1,000 miners and their families from Newport, Mon., came to Oxford, and sailed down stream from Folly Bridge to Sandford Lock, where they disembarked and joined in community singing, supported by the Headington Prize Silver Band. In the Oxford Journal Stevens & Co., fuel merchants, advertised their new 20-ton coal trucks — “Oxford’s contribution to the stricken Welsh coalfields”. The Magistrates Court was regularly sentencing young men described as “miner of no fixed abode” for drunkenness, breaking and entering, and assault. Two young Welshmen bound over to keep the peace after a fracas outside the Palace Cinema were advised by the chairman of the bench to be more careful in future. “I am informed that owing to your nationality you are liable to get excited”

It is perhaps difficult to realise that only fifty years ago men women and children, less than 100 miles from Oxford, were starving to death. Following an appeal by the Prince of Wales, the Lord Mayor of London set up a national relief fund at the Mansion House, and towns and cities all over the country were encouraged to participate. Oxford City Council responded without delay by setting up the Oxford Committee for the Relief of Distress in the Coalfields, appealing for food, clothing, bedding and money. Mr. R.R.Jordan of High St. Oxford visited the Rhondda on behalf of the Committee and on his return told the most appalling stories of starvation, tuberculosis and inadequate clothing. Early in 1929 40 sacks of clothing were sent to the Rhondda and 10 sacks to Maesteg. It soon became apparent that towns and cities such as Oxford could make the best possible contribution to the relief work by adopting a specific town or area, and this led to the adoption of Risca, Monmouthshire, in February 1929. Risca was adopted because it was the nearest coalfield to Oxford. Mr. Mason, squire of Eynsham Hall. instigated an imaginative training scheme for young men and boys from the Welsh Valleys, persuading local farmers to take in one or two for a few months, to learn the rudiments of farm work in order to prepare them for similar work in various parts of the British Empire. In January 1929 it was reported in the press that 250 men and boys from the coalfields had been found work in Oxford. Cash from the Oxford Committee was used by the Risca authorities to provide employment on public works. The chairman of the Oxford Committee, Mr.Bailey, suggested in one of his appeals to the community: “it might be possible to form a Welsh choir, which could give concerts, proceeds to go to the appeal fund”. Prophetic words indeed. In November 1928 Lloyd George visited Oxford and addressed the Oxford Luncheon Club; his subject was not the plight of the Welsh mining industry however; he addressed the Club on the implementation of the Treaty of Versailles.

The Party

It is not difficult to visualise a group of young and lonely Welshmen, some unemployed, living in digs, with little to occupy mind or body, drifting to the nearest pub, to drown their loneliness and disappointments in Morrell’s beer. Nor is it difficult to imagine that, after a few drinks, one or two would begin quietly singing some of the melodies learned in their homes and chapels. The next evening a few more lonely men would be there, and join in the singing. Thus was the Party born, at the Cape of Good Hope, a Morrell’s pub on the Plain, just on the Cowley side of Magdalen Bridge. Little did they realise that fifty years later The Party would still be flourishing.

The Party was first an octet, but it quickly grew and adopted the name of Cowley Male Voice Choir. The needs of these young men were noted by Frank Gray, Liberal M.P. for Oxford, and by a number of prominent citizens of Cowley. In particular, members of Cowley Congregational Church, led by their minister, the Reverend Whatley White, encouraged the singers to pursue their music-making and invited them to rehearse on the Church premises. A Mr.Taylor loaned them £1 to buy music; this is recorded in the very first set of accounts as having been loaned on 21 January 1929 and repaid on 29 May of the same year. (The first income and expenditure account covers the period to 4th June 1929; the total income was £5. 13s. 6d, raised entirely from members’ subscriptions, and expenditure totals £3. 4s. 3d – on music and postage).

Mr.Hardacre, conductor of the Cowley Congregational choir led the Welshmen for a few rehearsals, until they appointed their own conductor; he was at that time personnel manager at Pressed Steel, where many of the singers found work for the first time. Another well-known Oxford citizen, Alderman Fred Moss, gave them encouragement and financial support, eventually becoming President and continuing his association with The Party for many years, even after he had moved to Durban, South Africa. He was a native of Merthyr Tydfil, and therefore fully aware of the appalling conditions in the mining valleys. It was his company which built the Florence Park Estate, and whatever criticisms may be levelled at the quality of the building, this development met a critical need at a time when the rapidly-expanding motor industry at Cowley demanded homes for its workers. On the back cover of a 1931 concert programme Mr. Moss advertised new houses in Rymer’s Lane, Cowley, for sale freehold from £675.

In the late nineteen-twenties Morris Motors was able to satisfy its labour needs from local sources. The Pressed Steel Company was looking for a different kind of worker. The giant presses, imported from America, demanded large numbers of unskilled and semi-skilled workers and this demand was met by the influx of unemployed from South Wales and elsewhere. Hence most of The Party found work for themselves, and subsequently for friends and relatives, at Pressed Steel. The company pioneered the piece-work method of payment which has led to endless argument ever since, but at the time it appeared to hold the key to increased productivity. Some members of The Party were prominent in the early struggles for trade union recognition, when working conditions were appalling, and men could be called out to work at any hour of the day or night.

The bitterness which the young Welshmen brought with them from their homes inevitably boiled over on occasions; one member of The Party spent a night in the cells after a particularly stormy meeting. These early struggles at Cowley probably explain why The Party never accepted any form of sponsorship from the company; they feared that it would weaken their negotiating powers in an industrial dispute. However, relations between management and workers gradually improved and many of the company’s directors supported The Party as Vice-Presidents. But it has continued to guard its independence with fierce pride; perhaps this explains why it has survived.

In 1931 The Party changed its name to Oxford Welsh Prize Glee Singers. The “Prize” appears to have been dropped soon thereafter, and Oxford Welsh Glee Singers it has remained ever since, despite attempts by non-Welsh members to change it. This is hardly surprising when one reads the attendance register, bearing such names as Tom Bevan, Haydn Evans, Morgan Williams, Mel Davis Tom Jones, Billo Roberts, Howell Thomas, Gwyn Lloyd, Wynn Jones, and, for fouteen years as conductor, Willie Davies. Despite its name, The Party had no glees in its repertoire, and sang very little Welsh music to Welsh words – few of the young men from the valleys could speak their native tongue. The first printed constitution dated 1935 states that the annual subscription is six shillings, payable in two half-yearly instalments.

Pre War

The Party quickly made its name in Oxford and district, receiving much favourable press publicity. As early as 1933 a photograph of the choir appeared in the Oxford Mail, accompanied by an account of its victory in an Eisteddfod at Swindon, (The Oxford Mail cost one old penny in those days). In the early thirties an amateur choir could fill the Town Hall; for many years The Party held its annual concert there – this was before the days of universal car ownership and before the commercial development of the television set. On these notable occasions The Party was supported by eminent soloists, and programmes of those annual concerts make nostalgic reading for music-lovers -“Madame Jennie Ellis (London) Royal Premier Soprano, 13 times winner National Eisteddfod of Wales; Emlyn Burns (Nantyffyllon) Tenor, 9 times winnner National Eisteddfod of Wales, B.B.C. Artiste, Gold Medallist; Hywel Emlyn Jones (Swansea) Baritone, 6 times winner National Eisteddfod of Wales, B.B.C. Artiste.” The fees paid to these artistes were infinitesimal by modern standards, and were the subject of earnest and lengthy debate at committee meetings. The concerts were chaired by a prominent Welsh personality from City or University, supported by the Mayor, and were reported at length in the local press. The last Annual Concert took place in 1939 at St. James’ Hall, Cowley, and was not re-instated after the war, no doubt because of changing public tastes and habits.

Welsh choral traditions were firmly rooted in the founder members, They met for rehearsal twice weekly, and during the run-up to an important concert or competition extra rehearsals were called. A high percentage of attendance was expected, and the minute books record members being reprimanded and even dismissed for failing to achieve the required level of attendance. The 1935 constitution laid down that members had to attend two-thirds of all rehearsals in order to qualify themselves to take part in a concert. The committee was also extremely active and conscientious, in the early years meeting twice monthly, and the well-attended Annual General Meeting was held in October each year.

The competitive tradition was prominent in pre-war years, and The Party competed in eisteddfods and music festivals in many towns. One of it finest achievements in this field came in 1938. when it entered for the first time the Welsh National Eisteddfod, held that year in Cardiff. The Welsh National included a class for exile choirs and The Party, under Willie Davies came second to the Hammersmith Welsh Male Voice Choir. The following year The Party again excelled itself in winning first prize at the Northampton Festival. The adjudicator Armstrong Gibbs was moved to say that it was one of the finest male voice choirs that he had ever heard; he had not heard notes more correctly sung in all his career. There is nothing like competition to bring out the best in a choir. Coach journeys to and from competitive festivals were occasions of great fellowship, often the singing would continue non-stop on the return journey, particularly if The Party was bringing back a trophy. All the joys of communal music-making were there – the comradeship, the jokes, the laughter, the leg-pulling, the beer and smoke, and the singing.

Competitive singing engaged only a portion of The Party’s time and talents, Its main activity was the presentation of popular choral music to any organisation planning a fund-raising event, or just wanting an evening’s entertainment. Churches, chapels, schools, colleges, old peoples’ homes, hospitals, scout halls, sports clubs, workingmen’s club, Y.M.C.A., Salvation Army, Red Cross, Oxford Prison – the list is endless. Concerts were not confined to Oxford City; in prewar years concerts were given in Abingdon, Banbury, Bibury, Burford, Faringdon, Kidlington, Newbury, Thame, Shipton, Witney, Woodstock, and probably many more not recorded in the scrap books. Audiences were often small, sometimes a mere handful, but this never detracted from the rewards and satisfaction of both performers and listeners. Frequently the audience would be invited to join in the singing of the popular numbers.

In those days a concert by an amateur male voice choir was news. Concerts were fully reported in the local papers, often with a degree of musical criticism reserved today for professional performances. a well-balanced, flexible and pleasant-toned team though breath intakes were a little obtrusive here and there, crisp attack and release and a ready capacity to convey the spirit of the music were conspicuous virtues”. One memorable performance was a concert in aid of the 1934 Gresford Colliery Disaster Fund, an event which inevitably moved the hearts of many members whose fathers and grandfathers had worked in the mines. The minute books sadly record the tale of concert receipts being misappropriated but eventually recovered and paid over to the Disaster Fund. A similar moving occasion was a concert in 1939 in aid of the Mayor of Oxford’s Distress Fund for Risca; star performer on this occasion was the late Sir Walford Davis, Master of the King’s Music, who played piano duets with Sir Hugh Allen, and spoke of the Welshmen’s “dynamic pursuit of making music”.

The progress of The Party was noted in the press “back home” from time to time. The Merthyr Express reported in 1937 that •the Oxford Welsh Glee Singers, 27 of its 28 members South Waleians, included Tom Jones of Merthyr, Haydn Evans of Pendarren, and Evan Jones of Dowlais. Tom and Haydn are still singing members. Another South Wales paper reported under the headline “Rhondda Conductor Honoured” the story of Willie Davies’ achievements at Ferdale, and then in Oxford where he was appointed conductor of The Party soon after his arrival; this report was prompted by a broadcast on the Western Region of the B.B.C. An even lengthier re~o~t describes in some detail The Party’s success at the 1938 Welsh National Eisteddfod under the baton of “an old Ferndalian”.

In pre-war days it was customary for the printing of concert programmes to be partly financed by selling advertising space to local firms. Mention has already been made of Alderman Moss’ building company; other firms who advertised in the thirties and are still in business today include Messrs Acotts of High Street, and Hall the Printer then in Queen Street. Advertisers who have since disappeared from the Oxford scene are F Cape & Co., of St. Ebbes and Wards House Furnishers of Park End Street. Some well-known buildings where The Party performed have also disappeared, including the original Cowley Workers Social Club, Tyndale Hall in Cowley Road, now the site of the Ministry of Social Security offices, and the Electra Cinema in Queen Street. Mention should also be made of the Village House, a lodging house which flourished fifty years ago on the corner of Between Towns Road, opposite the Swan. This was the first port of call for many of the young Welshmen on their arrival at Cowley; there they found rest and refreshment, and news of relatives and friends who had preceded them on the great trek.

The growth of the car factories at Cowley during the thirties enabled most of the Welsh exiles to find work there, and they began to put down roots, becoming engaged, marrying, raising families, buying Mr. Moss’ houses on the Florence Park Estate, some bringing relatives up from South Wales to live with them. Relatives and girl friends joined in the life of the choir, supporting them at concerts and competitions, even turning up to listen and criticise at rehearsals. The strong family units of the South Wales mining communities were re-established in Oxford, east of Magdalen Bridge; by the outbreak of war the men who had emigrated from the valleys on foot and on bicycle a decade earlier had been accepted into the community and were making their own unique contribution to the social and cultural life of the City.

War

The outbreak of war in 1939 brought problems to The Party. Although many of its members were in protected occupations, they had to work long hours, on awkward shifts. Others were called up for military service, and The Party had to face the possibility of disbanding for the duration of the war. It did not take the members long to realise that they could perform a valuable morale-raising function – concerts for troops in camp and in hospital, concerts in works canteens, fund-raising concerts to provide comforts for servicemen and refugees. Nor were the needs of The Party’s own members overlooked; a comforts fund was set up and donations were regularly sent to serving members. Despite abnormal wartime stresses and strains, the chairman Morgan Williams and the conductor Willie Davies kept The Party going. When Roy Wagstaffe, the accompanist, was called up for national service a Mrs Kathleen Davies quickly stepped into the breach. Programmes were no longer printed. Transport to concert venues created problems owing to fuel-rationing. Winter journeys in the blackout could not have been pleasant. The Party’s services were constantly in demand, and despite all the problems, the demands met willingly and conscientiously. Because of its depleted strength, The Party frequently combined with other local choirs, one of which, The Cowley Conregational Womens Own Choir was conducted by Mrs Williams, wife of The Party’s chairman.

The Party was caught up in some of the more emotional events in war-time Oxford. It took part in a pageant at the Town Hall in 1942, promoted by the Ministry of Information to highlight the importance of women’s work. Among those appearing on the platform were actors Roger Livesy, Eric Portman, Robert Beattie, Leslie Howard, Leslie Banks and Ralph Richardson. The Party sang the Dachau Anthem, a work composed by a young Austrian musician while he was held in a concentration camp. It took part in 1943 in Oxford’s Salute to The Red Army – a parade through the streets of the City, followed by a concert at the Town Hall, where The Party joined with fervour and enthusiasm in the singing of the final item “The Internationale”. Among those present were Brendan Bracken, Minister of Information, and Quintin Hogg, Oxford’s member of Parliament. The Party’s wartime repertoire included not only the lnternationale but also The Stars and Str.ipes, the latter being a regular finale at concerts for American servicemen stationed at Cowley Barracks and the Churchill Hospital. It sang at a Labour Party May Day Parade and gave its services at a number of concerts in aid of the 35th L.A.A. Regiment Oxford Prisoner of War Fund. It participated in a number of Sunday evening concerts organised by the City Parks Department as part of the Holidays – at – Home campaign. One such concert in the Town Hall had unfortunate consequences. The audience, 900 strong, consisted mostly of young people, and The Party appears to have misjudged the mood of the occasion. A section of the audience disrupted the performance so persistently that The Party eventually walked off the platform, led by an angry Willie Davies. This incident was reported at great length in local papers, and was followed by a shoal of letters to the editor, arguing the pros and cons of the young people’s behaviour. It was a painful experience for the organisers and The Party.

Letters of appreciation from many sources are recorded in the scrap books. One reverend gentlemen wrote pointing out that the members had given freely of their limited spare time to give pleasure to others, even though they were working long hours in the Cowley factories, producing armaments for British troops. The Party’s activities in both fields represent a commendable contribution to Oxford’s war effort.

An Alan Course cartoon, courtesy of The Oxford Mail

Post War

The return to peace-time conditions in Oxford mirrored the traumatic experiences of society in general struggling to re-orientate its daily life to peaceful ends. The Attlee Government put in hand the social revolution which will provide historians with material for generations to come. The University was filling up with young men returning to academic life after living through the horrors of war. The Cowley factories began the painful process of converting production from armaments to motor cars. The end of the war put an end to the uneasy peace between the management and labour and the development of post-war industrial relations was punctuated by strikes. Lord Nuffield’s autocratic style of management surrendered to the growing power of the unions within his factories.

The Party had its own problems. It welcomed back members from active service and others who had been forced to resign during the war when shift working clashed with rehearsal time. The young men who had settled in Oxford in the late twenties were now approaching middle age and had acquired families and other responsibilities. Some had lost their original enthusiasm for singing, others had developed interests which commanded higher priority. One or two members resigned for health reasons, and sadly a few gaps appeared through death. The resignation of Willie Davies as conductor in 1950, after fourteen years of loyal service, was seen by some as a mortal blow. At the critical time when survival appeared to depend on the recruitment of another generation of singers the almost universal ownership of motor car and television set was revolutionising social habits; young men were no longer prepared to sacrifice time, money and effort in the cause of amateur music-making. Inevitably numbers fell and average age rose – a recipe for disaster.

And yet the Oxford Welsh Glee Singers survive, and have many notable achievements to record during the second half of its fifty years of song. The competitive spirit flourished and in the early nineteen-fifties The Party won the male voice choir competition at the Kingswood, Bristol Eisteddfod three years in succession. In 1952 it combined with The Morris Motors Male Voice Choir to present a Coronation Concert at the Clubhouse in Crescent Road, Cowley. This event was chaired by Reg Bishop, the genial manager of Nuffield Press, and among the soloists was a young violinist, Ralph Holmes, who has since won international acclaim. In 1955 it broadcast twice within 48 hours. On the 30th November, it took part in a Welsh magazine programme recorded for transmission the next day in the B.B.C. Overseas Service. In the course of this programme Haydn Evans, the secretary, broadcast a message to Fred Moss, President, in South Africa, in which he said: “we are bound together in the common love of good music, and the good fellowship which it brings”,

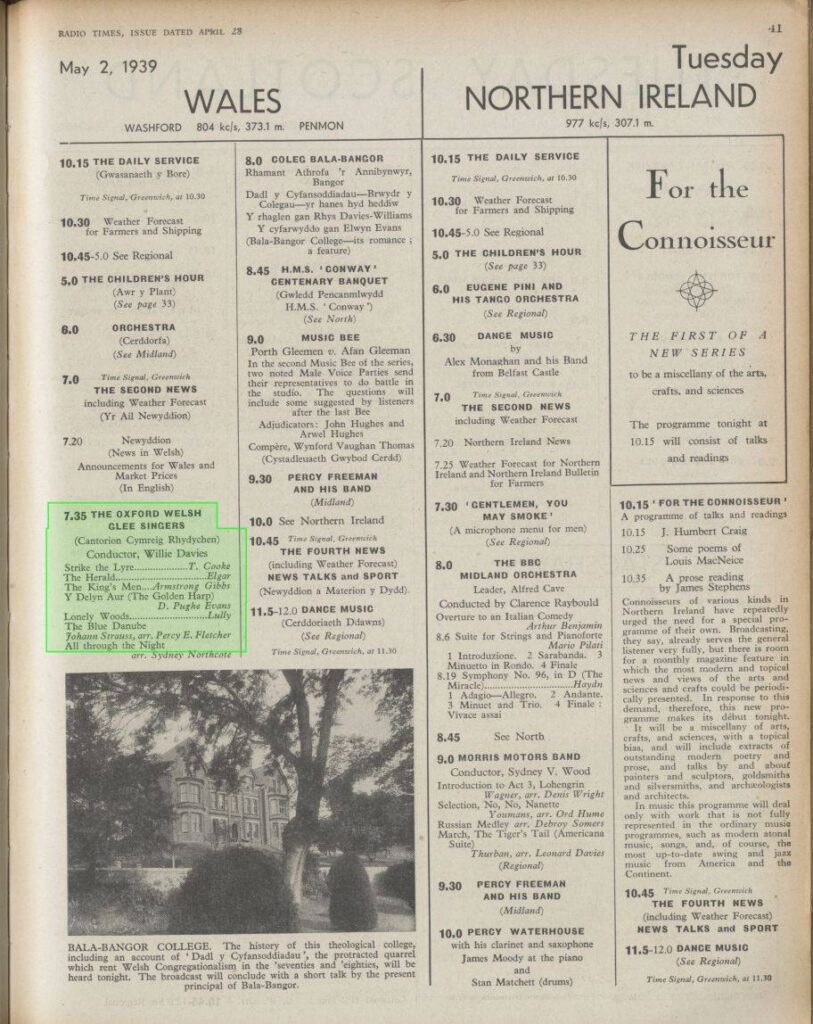

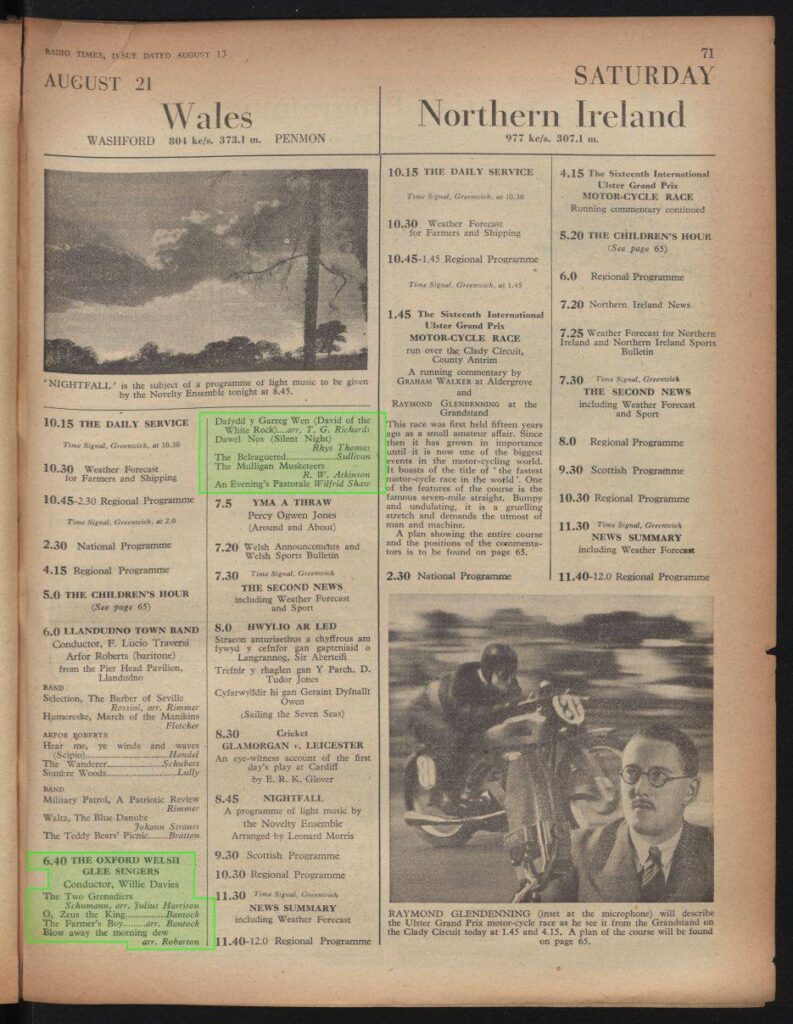

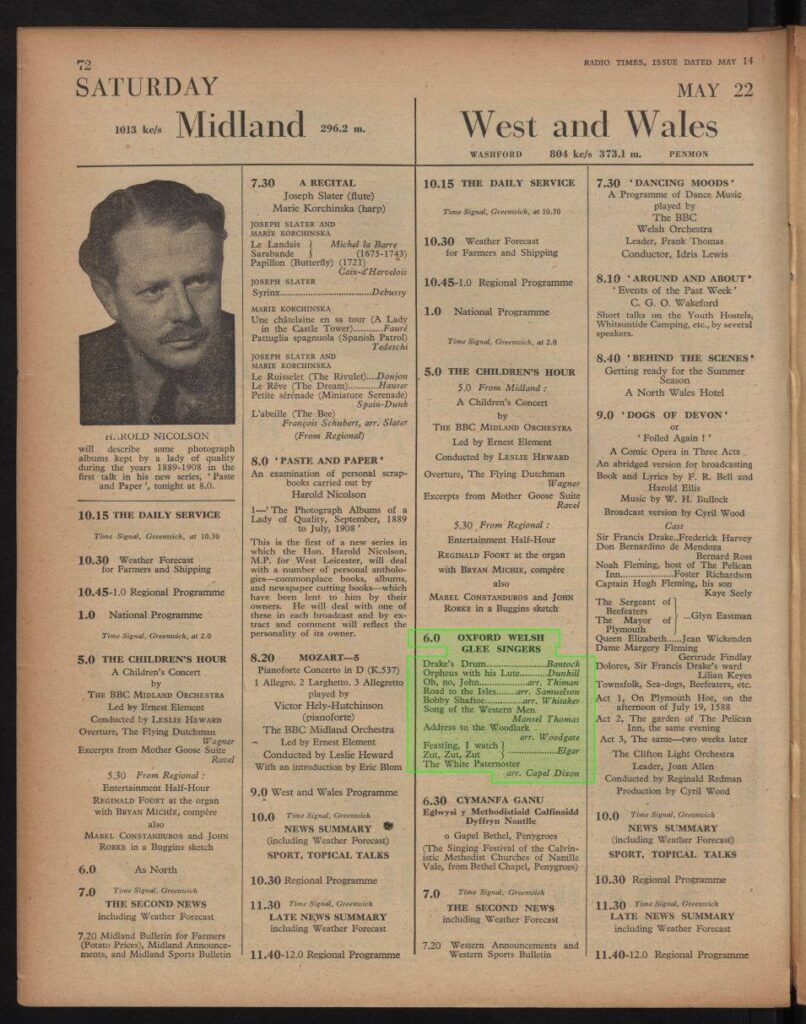

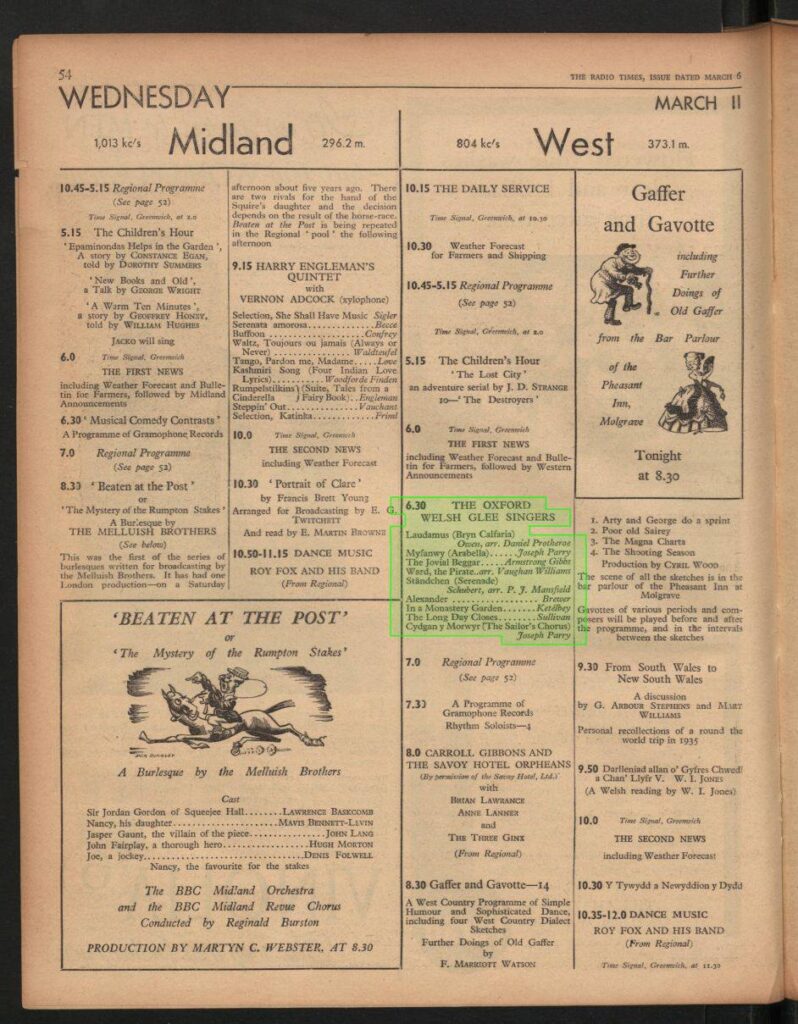

Then on the 2nd December they were heard on the B.B.C. Home Service in a 20 minute recital of part songs from their extensive repertoire. They were no strangers to the broadcasting studio, having first broadcast in 1936, and again in 1937, 1938. 1939, 1949 and 1950.

1956 The Party made its debut on television, as a member of the Oxford team competing in an inter-town knock-out variety competition called “Top Town”. The Oxford team was selected after a number of preliminary concerts; at one of these, in Abingdon Corn Exchange, the Oxford Mail reported “the evening was stolen by a group that has recently joined the team the Oxford Welsh Glee Singers, whose unpretentious and unified singing was the most polished performance in the show”. Oxford’s opponents were Newport, Mon., and the show went out live from the B.B.C. Manchester studios, at that time housed in a converted chapel. As all the performers were amateurs it is remarkable that the show ever got on the air, the chaos in the studio had to be seen to be believed. Among the Oxford team was the late Alan Course, a man of great wit and talent, whose act consisted of drawing cartoons on the bare backs of young ladies. During rehearsal breaks Alan instructed The Party in his own “Russian” version of Sospan Fach; if this had been in the Oxford programme it would have won every prize in sight. After the show the Oxford team joined with its conquerors from Newport in a night of conviviality which will long be remembered by those who were able to stay the course.

In between these more exciting events The Party continued to offer its services for many local causes. Since the war it has averaged about twelve concerts a year, mostly to small intimate audiences who appreciate its style of music making. For the sake of variety The Party interspersed its own contributions with solo items, and the solists were generally drawn from the ranks; these were the characters who contributed so much to its success, year after year. Morgan Williams, founder member, the perfect chorister, 100% committed, punctual, attentive, loyal, for many years secretary, then chairman until ill-health intervened, guide, counsellor and comrade to all his colleagues, including successive conductors. A 1942 press cutting reports a concert at Ruskin College, then in use as a war-time maternity hospital, and concludes “it was here, 14 years ago that Mr. Morgan Williams, now secretary of the choir, presided at meeting at which they were formed”. He had a mellow baritone voice which has echoed round halls and chapels in Oxford and district for the best part of 40 years. Despite the tragic loss of his only daughter, he continued to give all to the choir, while his wife demonstrated a similar devotion as conductor of the Cowley Congregational Womens Own Choir. Harry Dunkley, not one of the young Welsh immigrants but an older man who has spent his career with the Oxford City Police, retiring with the rank of constable; a fine figure of a man, taller than average, a stern expression exaggerated by his large moustache, undoubtedly a steadying influence on some of the younger choristers. He was for some years chairman of The Party and on more than one occasion put his hand in his own pocket when funds had run out. Harry died in 1950, mourned by his fellow-choristers; the minutes of the committee held on the 26th September that year contain a moving tribute to his 17 years of service to The Party, ending “Well done thou good and faithful servant”. Harold Bull, leader of the first tenor section for many years. As a young man he had touched the fringes of professionalism; in a 1938 programme his credentials are recorded as “Gold Medallist, Madame Paling’s Scholarship, London”. He had regrettably not looked after his voice, and in later years had a limited range; but within that range he could produce notes to rival any nightingale. His repertoire too was somewhat limited, but his favourite “There is a lady sweet and kind” always promtped a storm of applause. Harold was dubbed “Clark Gable” because he had Gable’s ears and moustache; but Gable’s gravel voice could not be further removed from Harold’s sweet tenor. Haydn Evans, bass-baritone, with a voice as rustless as the famous iron bridge at Merthyr, from whence he came. A great servant of The Party, successively committee member, secretary, chairman. Like a number of his colleagues who spent some years in the press shop at Pressed Steel, his hearing was not perfect and this occasionally affected his intonation, but what a voice – if he had been willing and able to accept the discipline of professional training he would have rivalled Geraint Evans. Now approaching three score years and ten, still able to charm and soothe a critical audience. Tom Jones, the only founder member still active in The Party, another loyal chorister, unambitious but reliable, with a true tenor voice, even at the age of 73. It is doubtful if his more famous name-sake will still be singing at that age. Tom is equally well-known for his performances on Oxford bowling greens. Arthur Hayes, a most loyal servant and for years deputy conductor, while his wife served equally loyally as accompanist. Arthur’s personal ontribution to concert programmes was the humorous monologue; although this type of entertainment belongs to another age, before radio and television, his tales were beautifully told, the tension built up with professional skill and aplomb until the pay-off line, never failing to generate spontaneous laughter even among his fellow-choristers who had heard the stories many times before. Walter Davies, a Welshman to his fingertips, who arrived in Oxford by a very different route from the founder members. He came from a poor family background in Barry but a sharp intelligence eventually led him to Harlech College of Adult Education, and then, after a period at the Educational Settlement in Merthyr, he was appointed probation officer at Oxford in 1941. He quickly made contact with his fellow Welsh exiles, and became a much respected and loyal member of The Party, holding the office of Treasurer for many years. Walter will always be remembered for his immaculate dress – pinstripe suit, bow tie and spats even on the most informal occasion, He was a loyal and conscientious second bass occupying pole position – at the right hand end of the front row — throughout his time with The Party. He had to tolerate a certain amount of ribald ragging from some of the younger members because of his calling but he took it in good part, and was greatly missed when he moved to Southend, where he died in 1975.

A further concession to variety in concert programmes was the regular inclusion of lady soloists who not only performed on their own, but frequently joined with a member of The Party in rendering duets. Many followers of The Party will remember Ivy Barratt, Dorothy Hutchinson, StelIa Hitchins, Jean Gould and Betty Lawrence. Male voice duets and quartets were also a regular feature; Harold Bull and Haydn Evans would probably make the Guinness Book of Records for their innumerable renderings of “The Two Gendarmes”. Occasionally The Party joined with professional artistes; they appeared at Banbury with Sandy MacPherson the concert organist and Harvey Allen the operatic baritone. They were invited to broadcast with the George Mitchell Glee Singers from Oxford Town Hall. They have met many of the finest musicians in the country at competitive festivals; adjudicators of the calibre of Herbert Howells, Leslie Woodgate, Bernard Rose, Armstrong Gibbs, Sydney Northcote and Eric Thiman gave them invaluable advice and encouragement.

The Party 1954: conductor Richard Bedwin

In the course of its fifty-year history the choir has had ten conductors, and pride of place must go to Willie Davies, conductor for fourteen years from 1936. Willie was the archetypal Welsh choral trainer — small, neat, dark, bright eyes, intense expression, utterly absorbed and dedicated in performance. Born and bred to choral music in Ferndale, Rhondda, he was conductor of the Ferndale Ladies Choir and deputy conductor of Pendyrno Male Voice Choir. He lost his job when the Ferndale colliery closed down, and decided to follow some of his friends to Oxford, where he was soon appointed conductor of The Party, even before he found work. For his appearance as conductor at the 6th Annual Concert in Oxford Town Hall a dress suit was hired for him, paid out of choir funds. Through the members’ connections at Pressed Steel Willie eventually found a job there. He did not enjoy the best of health, his lungs being affected by silicosis, but he was a dedicated and respected choral trainer. He has been accused of being a pot-hunter – more interested in competitive festivals than the run-of-the-mill charity concert; but Willie knew that in competition a choir will achieve a standard of performance way above the average and just occasionally he inspired that perfect performance which is the goal of any conductor.

Mr Bernard Maliphant, the present secretary of The Party, has gathered together a catalogue of 250 pieces of music, all of which have been in The Party’s repertoire at one time or another. Some much-loved pieces have been in the repertoire for half a century, some for only a short time. Some were learned for a competition and then quietly buried away in the choir library. A few were rehearsed but never included in a public performance. Every type of music suited to male voices is represented in the catalogue – Welsh folk songs and hymns, English part-songs, negro spirituals, sea shanties, operatic choruses, sentimental ballads, carols, comedy numbers, and competitive pieces, often written for the occasion by contemporary composers. This enormous repertoire provided the opportunity for extensive and exciting programme planning, but examination of concert programmes reveals a lack of imagination and a safetyfirst approach. A 1931 programme includes a Welsh piece “Y Delyn Aur” a stirring chorus “Comrades in Arms”, and the Soldiers’ Chorus from “Faust”.

These three pieces reappear at regular internals throughout the next forty years. Nothing wrong with that, the members will say, our public still enjoy them. Programmes sometimes had to be selected with particular care, to suit the occasion; for instance at a concert to mark the formation of the Oxford & District Welsh Society in 1954 the programme was made up almost exclusively of Welsh music, with Welsh words laboriously learned. The choice of music was not always entirely appropriate. At a concert performance in Oxford Prison on a Sunday afternoon in 1953 the programme included the popular ballad “Bless this House”. The choir was left in no doubt as to the popularity of this piece, when the words of the second verse rang out – “Bless these walls both firm and stout, keeping want and trouble out …”. Another example of spontaneous humour occurred when The Party were booked to give a concert in the village hall at Wootton, Oxon. In accordance with standard drill the coach went round Headington and Cowley calling at pre-determined pick-up points one of which was the the Swan Inn at Cowley. While waiting for members to arrive Jack Evans, already on board, left the coach and went into the Swan to buy cigarettes. The coach moved off without him, and his absence was not noted until The Party had formed up on the platform in the village hall, by which time it was too late to go back and find him. The choir proceeded to sing through its programme, and as the conductor lifted his baton to begin the final item, Jack walked onto the platform, and without batting an eyelid took up his place next to brother Haydn in the front row of the first basses. The title of the last item was “The Happy Wanderer”. The leg-pulling on the return trip was merciless, but Jack took it in good heart and explained that it was by no means easy to thumb a lift from Cowley, Oxford, to Wootton, Oxon, on a dark wet Saturday night, particularly when wearing evening dress. He is an extremely versatile character, his versatility was recorded for posterity in 1961 when he was included in the list of officers as “librarian, registrar, tape recorder and electrical adviser”.

A typical broadcast programme –B.B.C. Home Service 25 November 1955· · · · 6.30 THE OXFORD WELSH GLEE SINGERS

Conductor, Richard Bedwyn

Counting the goats (Welsh folk song) – arr. Caradog Roberts

The Herald – Elgar

The Silent Land – Leslie Woodgate

Music when soft voices die – Edward Bairstow

Peter, go ring dem bells – arr. Granville Rantock

Bushes and briars – arr. Vaughan Williams

When evening’s twilight.. – John Hatton

Fain would I change that note – Vaughan Williams

(BBC recording)

Proposed and Seconded

This brief history owes much to the minute books which have been meticulously written up and carefully preserved. It is a matter of speculation how this group of young Welshmen had the knowledge and expertise to record The Party’s activities so accurately and thoroughly. The minutes are written in legible longhand, and follow the accepted formula. Where was this skill learned, what was their model? It has been suggested that some of them would have learned the craft as members of miners lodge committees back home. The detailed minute books cover the periods 1935 – 1955 and 1964 – 1975; the missing minute books are probably quietly gathering the dust in some former secretary’s cupboard under the stairs. The minutes record the unusual routine matters, which one would expect to find in an organisation of this kind -criticism of low attendance at rehearsal, pleas for punctuality, pleas for new members, criticism of deportment on the concert platform, criticism of the conductor for his choice of programme, effusive congratulationsto the treasurer on his masterly presentation of the annual accounts, propositions for fund-raising activities and social events. However, they record much more, since they reflect the personalities of officers and committee members, their agreements and disagreements, their desire to serve, their determination to succeed. A few quotations will perhaps help to capture the flavour:

· · · 3.11.1935 it was decided that The Party would pay for the fares of unemployed members (to Swindon Eisteddfod)

1.12.1935 the following correspondence was read – letter from Madame Jenny Ellis reminding The Party that she was now free for engagements.

3.12.35 Mr …….. was written to with regard to the rumour that he was suing The Party

15.12.35 Messrs ….. and …….. were appointed to call on Mr……. to enquire what progress had been made with regard to repaying his debt to The Party. It was proposed, seconded and carried unanimously, that the caretaker should be given a Xmas box of ten shillings.

14.1 .36 the position of Mr …….. was discussed and as he was not in permanent work Mr …….. of Pressed Steel was to be written to by the secretary asking him if anything could be done.

26.1 .36 the secretary was requested to see Mr ……… with regard to a vacancy at The Radcliffe Infirmary.

5.7.36 the secretary to write to Dr. Tom Armstrong saying that we would appreciate a visit from him on one of our practice nights.

27.9.36 Mr brought forward a complaint that visitors to the practice room distract the attention of members of the choir. Resolved that members should advise their friends that quietness and good demeanour was essential.

28.9.37 Mr. H.Evans was incorporated (sic) on the committee

30.1.38 it was agreed to write Father Whye re chimney (as curate at Cowley he was responsible for St. Christopher’s School, where the choir rehearsed).

27.2.38 it was agreed that Mr. Hengoed be approached re daffodils (presumably for a St.David’s Day concert)

1.7.38 it was decided to invite the Rhythm Rascals Harmonica Band, provided they give their services free

10.7.38 the coach to leave Oxford at 5.30 a.m. (for Welsh National E isteddfod)

4.4.39 agreed that the conductor should receive a grant of £4 towards the purchase of a dress suit.

24.9.39 (outbreak of war) the future of the choir was discussed at some length but it was unanimously agreed to carry on to the best of our ability. It was agreed to write to Father Whye regarding a reduction in rent (of the rehearsal room).

13.9.40 Mr.Moss, President, suggested getting in touch with Mr.R.B.Cole for the purpose of giving an entertainment to the troops under his command.

22.5.42 resolved that the name of the choir should remain the Oxford Welsh Glee Singers.

25.9.42 (A.G.M.) resolved that £10 be invested to form the nucleus of a Building Fund with the object of obtaining a rehearsal room of our own. Carried unanimously

7.1.44 the conductor reported that next practice night he would be engaged in Home Guard duties.

6.10.44 proposed and seconded that the secretary be instructed to send ten shillings to each member serving in H.M. Forces.

8.6.45 the secretary reported that he had been unsuccessful in his application to the Regional Transport Officer for permission to travel to Leamington by private coach.

20.7.48 after a long discussion (on travelling arrangements) it was proposed and seconded that all members of the choir pay full fare, wives, children and sweethearts travel free, others may attend at their own expense.

5.10.48 the treasurer reported that there were insufficient funds in the general account to settle the amount owing to Messrs Drings, for the hire of the coach on 28 Aug. It was agreed to write Messrs Drings asking their indulgence for a little while

24.4.49 moved and seconded that the Building Fund become extinct and the monies held in such Fund be merged in the General Fund

17.11.50 letter from Mr ….. requesting a loan of £22 to purchase a dress suit, so that he could be properly attired at future concerts. Request declined

14.8.51 ….this did not meet with the approval of Mr and he thereupon informed the committee that he would resign his office, and he left the meeting. He was prevailed upon to return and further discuss the matter. There was further heated discussion during which Mr tendered his resignation, and the meeting was in disorder. Eventually calm was restored

2.2.54 In view of Mrs. Hayes’ forthcoming happy event, every effort should be made to obtain a temporary pianist. (Everyone was delighted when Eileen and Arthur Hayes, accompanist and deputy conductor, were blessed with a son, rather late in life).

8.2.54 Mr. J. Evans kindly donned the specimen dress suit for members to assess its worth as regards style, texture. The examination was duly carried out, and it was the opinion of all present that if fitted in every way the requirement of The Party (at £4.9s.6d a suit!)

12.1 .67 the treasurer reported that funds had fallen low at this period due to the £50 given to the Aberfan Appeal Fund.

In minute books, scrap books and concert programmes the names of Oxford citizens prominent in many walks of life appear, supporting The Party in various ways. Vice-presidents included Capt. Bourne, M.P. for Oxford before the war, and Bunny Cole the Oxford solicitor, who later commanded the 35thL.A.A. Regiment. Civic dignitaries included Alderman Fred Moss, Alderman C.H. Brown, Alderman Skipper, who first persuaded The Party to entertain the inmates at Oxford Prison, Alderman W.M.Gray, and Alderman Mrs. (later Lady) Townsend. The church was represented by vice-presidents Rev. Maurice Beauchamp, Father Whye, and Reverend Whatley White, and the University by R.H.W. Jones, J.G. Edwards, both of Jesus College, Prof. Gilbert Murray and Dr. Micklem. The car industry was represented by Lord Nuffield, who regularly appeared at the Morris Motors Musical Festival, and presented a handsome shield for the male voice choir competition, won by The Party on several occasions; Mr. Woodcock, Works Manager and later managing director; and Messrs. Shuttleworth, Wood and Cairns, directors of Pressed Steel. Jack Thomas was _closely associated with many members as first secretary of the Oxford branch of the Transport and General Workers Union. Jack was a great fighter in the cause of fair play and dignity for the manual worker in the Cowley car plants, he later bacame a vice-president of The Party, and chaired a number of concerts. He was in a sense one of them, since he too had left his South Wales home in 1936 and travelled to Oxford to take up his new appointment.

The Party 1975 : conductor John Battershell

The Party 1975 : conductor John Battershell

Jubilee

It was inevitable that a group of young men arriving fifty years ago in what for them was a foreign city, should seek each other’s company, particularly since many of them already knew each other, or relatives of each other; news in letters from home was passed round, there was comfort in sharing good news and bad with others from the same background. The eventual arrival of relatives, including sometimes elderly parents, meant that an established pattern of family and community life was transferred from The Rhondda to East Oxford. The Party is a natural expression of that established pattern, since music-making is very much part of its heritage; without it, something else might have taken its place, something more selfish, less satisfying, less conducive to survival. For some of the older members choir pratice has become a habit, and breaking a habit of forty years or more can be painful. In celebrating its Golden Jubilee The Party is marking the survival of Welsh culture in an English provincial town for 50 years. Why does it survive, in spite of a long war and a post-war revolution in people’s habits and standards of entertainment? It has survived when other music-making organisations have perished; a perusal of old programmes reminds one that Morris Motors Band and Pressed Steel Band have both disbanded, despite their enjoying a measure of sponsorship. Members have always paid for the privilege of belonging; for many years even the conductor and accompanist received no honorarium. It is a truly amateur body, any fees and prize money are paid in to The Party’s funds to help meet running costs.

For years members rehearsed twice and three times a week in cold, badly-lit school halls, with leaking roofs and pianos long past their prime. Rehearsals followed long slogging days in the factories, half-deafened by the clatter of presses, when it would have been so much easier to go home and spend the evenings with wife and children.

The demand for The Party’s services continues unabated, it does not have to seek engagements, requests pour in. In the past 15 years it has given concerts in 35 towns and villages, mostly in Oxfordshire. Yet, unless a new generation of choristers can be found, commonsense suggests that The Party must die. It is too much to hope that young people will turn to this kind of music-making, when professional perfection is available at the touch of a radio or television switch, It is doubful if sponsorship would bring in the necessary new blood. Survival to date undoubtedly stems from its Welsh origins; there is a rather symbolic irony in the recent election of a Scotsman as its chairman.

Whatever the future may hold, The Party can be proud of its fifty years of service to others, its fifty years of song. The constitution defines its objects as the study and appreciation of the art of music and the promotion of good fellowship among music lovers. Without doubt those laudable objects have been achieved.